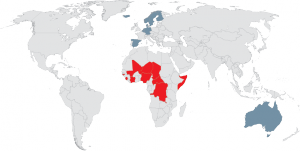

The annual Save the Children report, State of the World’s Mothers 2014, ranks 178 countries on several factors related to the well-being of both mothers and children. The top ten countries in 2014 are dominated by European entries, with Australia being the only non-European country, tied in ninth place with Belgium. The ten worst places for mothers and their children are all in Africa.

The top three countries to raise children are Finland, Norway and Sweden, with the other Nordic countries of Iceland, and Denmark in in fourth and sixth place respectively. In general, the report states all the countries in the top ten scored very highly for mothers’ and children’s health, educational, political, and economic status.

This is a reverse of the conditions for mothers and their children in the bottom countries. According to the report, the greatest disparity between regions can be seen in the lifetime risk of maternal death figures. In Central and West Africa, 1 women in 32 is likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth. This is five times the risk facing women in South Asia (1 in 150), and almost 150 times the risk of women in industrialised countries (1 in 4,700). The report also stressed the huge gap between rich and poor countries, several of the lowest ranked countries are also among the world’s poorest.

Let’s put the spotlight on some popular expat destinations.

The Netherlands (5th)

Northern European countries ranked highly across all categories, with the Netherlands being no exception. The lifetime risk of maternal death (the probability a 15 year old girl will die in her lifetime from a maternity related cause) is 1 in 10,500 and the under-5 mortality rate is 4.1 per 1,000 live births.

Dutch children have been described as the “happiest on earth”, according to a UNICEF report released last year. High educational standards, childcare support to encourage women back to work, and childcare commonly shared between both parents all help to boost the Netherlands’ ranking.

Australia (joint 9th)

A perennial expat favourite, Australia attracts many families with its climate, outdoor lifestyle, and English-speaking opportunities. The lifetime risk of maternal death is slightly high than the Netherlands at 1 in 8,100. The under-5 mortality rate is 4.9 per 1,000 live births.

Looking at the HSBC raising kids abroad survey, Australia performed consistently well on measures relating to the health of expat children – with seven in ten (70%) expats seeing an improvement in their children’s health and wellbeing since relocating, compared to a global average of 56%.

Spain (7th)

Typically Spain attracts British expats to its sunny shores, with around several hundred thousand making their homes there. Spain has one of the lowest maternal death risks, with 1 in 12,000 15-year olds dying of maternal causes in their lifetime.

Spain ranked number one for the cost of childcare in the HSBC raising children abroad league table, parents also reported their children were more outgoing in Spain, were learning a second language, and had a wider circle of friends than they did in their home countries.

United Arab Emirates (52nd)

The UAE, specifically Dubai and Abu Dhabi, attracts expats with lucrative job opportunities, and more are relocating with their families than ever before. The lifetime risk of maternal death is 1 in 4,000, and the under-5 mortality rate is 8.4 per 1,000 live births.

According to the raising children abroad league table, the UAE is improving as a place to bring up children, with 7 in 10 (72%) of parents surveyed saying they felt their children were safer there than at home. However, the high cost of education and childcare are putting parents off – those expats who leave the country after a short time tend to be those with children.

What can be done?

Save the Children is urging governments and international agencies to increase funding to improve education for all children, to increase access to child and maternal health care and to boost economic and political opportunities for women.

In industrialized nations funding should be used to improve healthcare and education access for disadvantaged children and mothers.